- Home

- Michael Cleverly

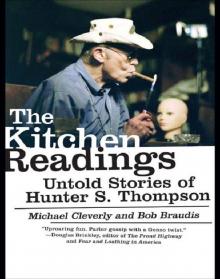

The Kitchen Readings

The Kitchen Readings Read online

The Kitchen Readings

Untold Stories of Hunter S. Thompson

Michael Cleverly and Bob Braudis

This book is dedicated to the memory

of our dear friend

Tom Benton

Contents

Introduction

Two Beginnings

Cleverly Chats with the Doctor

Bob Tells Us About Maria and Lost Love

Cleverly Tells Tales of Tex

Wayne Ewing Relates Tales That Make One Wonder

Braudis Explains the Birth of Shotgun Golf

Hunter Goes to War, and Doesn’t Much Care for It

Hunter’s Friend Dabbles in the Business and Pays the Price

Cleverly Tells a Few Animal Stories

Braudis Describes Hunter’s “Hey, Rube” Moment

A Brief History of the Sheriff’s Squeeze

Hunter’s Adventures with “Duke,” a Gentleman of Dubious Character

Hunter Takes an Artist to a Filthy Strip Joint

Hunter and the Hot Veterinarian

A Cowboy Helps Hunter Out, Again and Again and Again

Growing Up Across the Street from Hunter

A Lawyer Learns from an Expert

The Mayor’s Daughter and an Awkward Moment

Cleverly’s Short Road Trip

The Sheriff Reflects on the Neighbor

Cleverly Explains How Hunter “Goes Off” Occasionally

Bob Discusses Hunter and the Secret Service

Cleverly Tells of the Lisl Auman Crusade

The Sheriff Investigates the Shooting of Deb

Cleverly Faces Fans Gone Wild

Braudis and Wheels

Sheriff Bob Relates Fun and Games at the Vail Clinic

Bob Describes a Mishap on Assignment

Bob

Cleverly

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Praise

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

The title The Kitchen Readings refers to Hunter’s writing process. He loved to hear his own words read aloud. He would write; his friends would read. This is how he edited, how his work evolved…on into the night. That process took place in the kitchen at Owl Farm, Hunter’s home in Woody Creek, Colorado. The kitchen was the center of life at Owl Farm and it was the engine room for Hunter’s literary juggernaut. The kitchen may indeed be the hub of many American homes—and though life at Owl Farm was Hunter S. Thompson’s life, it certainly was not traditional American fare, nor was it quite the life that might be imagined by the many thousands of Hunter’s fans. Hunter made himself the hero of his books. He also manipulated the tools of the information age to create a mystique that stood apart from his writing. Hunter has a huge base of people who love his writing and a second, perhaps even larger, fan base of people who are drawn to his mystique. Hunter’s admirers base their knowledge of him on three sources: his writings, the image he crafted in his writing and projected in his life, and the almost endless stream of superficial profiles created by journalists who would briefly visit Owl Farm and rush home to crank out their “Hunter Thompson in Woody Creek” story.

Doc, Cleverly, and artists Mary Conover and Earl Biss enjoy a quiet evening in the kitchen.

Over the years, we have watched Owl Farm visitors come and go, the famous and the forever unknown, celebrities and artists, intellectuals and fools. Many of them took a turn reading in the kitchen, and we were there. We were part of Hunter’s life on a daily basis.

Pitkin County sheriff Bob Braudis, one of your narrators, was Hunter’s closest confidant for many years. He was told that he had earned the right to “show up anytime” without invitation or notice, a reward for loyalty, professional problem solving, and tolerance. Hunter intimidated most people, but not the sheriff. Hunter and Bob came to each other as equals, and this created a healthy atmosphere that they both relished.

Hunter would use Bob to ease the tension during difficult business negotiations, or anytime, in fact, that it was to Hunter’s advantage for a guest in the kitchen to remain calm and unterrified. How bad could things get with the sheriff there? Bob would also act as interpreter. It took years for Hunter’s friends to get used to his mumble. Learning his language would occur through some sort of weird osmosis over a long period of time. At some point it would simply dawn on you that you could understand every word that Hunter was saying, while those around you were just staring at him and nodding or scratching their heads. First you’d ponder just how the hell this had happened, and then you’d begin to worry about what exactly it meant. Both Bill Murray and Johnny Depp managed to find a way to mimic Hunter’s speech while keeping it intelligible, an astounding feat, but not one Hunter was interested in duplicating. Bob Braudis was fluent in Hunter’s mumblese and would fill the interpreter role with diplomacy and charm. He could be counted on to keep to himself what transpired, and to offer an intelligent, objective perspective when needed.

In the 1970s, Hunter was in and out of the Roaring Fork Valley looking for stories, and he actually wrote some of them. Bob would always be there when Hunter returned, to give him the inside scoop on whatever had happened at home during his absence and to provide an honest sounding board for Hunter’s tales of his own adventures. The two men who rarely needed backup from anyone could lean on each other. Bob says that if you held his feet to the fire he’d have to say that Hunter gave him more than he gave Hunter, but neither of them kept a ledger.

Bob Braudis has been Pitkin County sheriff for the last twenty years and was recently elected to another term. Before that, he spent nearly a decade as a sheriff’s deputy and two years as a county commissioner. Bob came to Aspen seeking the life of a ski bum, but the ski bum life is that of a single man, and Bob had a family. After eight years he finally surrendered and found a “straight” job. That job was in law enforcement, and the rest is history.

Cleverly enjoying a beverage with Doc on the deck, perhaps straining to understand the words coming out of Hunter’s mouth.

Sheriff Braudis, not showing the strain of his friendships with

Your other narrator, artist Michael Cleverly, migrated to Aspen in the early seventies. Back then, Aspen was a classic ski town and still retained some of the charming qualities of small-town America. Aspen’s artists and writers were an intimate community, and it would have been impossible for Cleverly and Hunter not to meet. In fact, Cleverly’s studio was in the Aspen Times building, right next to the Hotel Jerome and its famous “J-Bar.” A hardworking painter needs a break sometimes, and quite often Hunter would be at the far end of the bar having “office hours.” Cleverly and Hunter shared many interests, and the two became close. Later Cleverly would move to a cabin in Woody Creek, just up the road from Owl Farm. Already friends, when they became neighbors Cleverly and Thompson found their contact evolving into an almost daily (or nightly) event. Hunter had someone he could trust just minutes away, and that meant a lot to him. Cleverly spent more waking hours in Hunter’s kitchen than in his own living room.

The stage for the earliest stories in this book is Aspen, Colorado. In the 1970s the J-Bar was the hip gathering place in Aspen. Movie stars mingled with construction workers, wealthy trust-funders with ski bums. There was a wonderful democracy about the town in general, and the J-Bar in particular. It was a comfortable atmosphere for artists and writers, and it was where we spent our “off” hours. It became the clubhouse. “The J-Bar” was our name for what was officially “The Bar at the Hotel Jerome.” Happy hour was “roll call,” and attendance was required. If you didn’t show up, people worried and got on the phone. The bar was the scene of many l

egendary events, and of some stories that can’t be told even decades later. Our friend Michael Solheim ran the place, the waitresses were all young and beautiful, and the bartenders were our buddies. It was a happy family of people whose only common denominator might have been their madness. Our gatherings there went on for years, maybe a little longer than they should have. We began to lose friends to rehab and jail. Eventually the hotel renamed it “The J-Bar” and lettered that on the windows. By then we had pretty much stopped going there. We gave it up to the next generation and the principal action moved down valley, to the Woody Creek Tavern.

Legendary Tavern bartender Steve Bennet and waitress Cheryl Frymire with young Bob and Doc; Cleverly with friend and neighbor Sue Carrolan. Sue was at Owl Farm with Cleverly the Friday night before Hunter died.

Waitress Cheryl with Doc and Johnny Depp. The Tavern staff got a little mileage out of the celebrities who visited.

The Tavern was located just over a mile from Owl Farm, so getting home from there was a lot safer than driving all the way back from Aspen after a hard night. The only word in the English language that begins to describe the décor of the Tavern is eclectic, but that doesn’t really do it. The slightly decaying Victorian opulence of the J-Bar was easy to envision; the Tavern was the polar opposite. The walls were covered with photographs, and newspaper and magazine clippings that went several layers deep. The visual chaos made it impossible for the eye to rest on the few pieces of framed art that shared the wall space. The place was basically an insult to Aspen snootiness; it looked as if the interior decorating decisions had been made with an eye toward withstanding a chair-swinging barroom brawl rather than to make the customers feel special. The fact that it was located in the middle of a trailer park was perfectly consistent with its overall “no-frills” working-class ambience. Of course, by the time Hunter died, Woody Creek had seen its fair share of celebrities move in, along with the building of monster homes by the superrich. But in the beginning the Tavern was a place for regular folks, where Aspen types came on safari, and Hunter was king.

The Kitchen Readings are tales of events that took place in the Jerome, the Tavern, and, of course, the Owl Farm kitchen. There are also stories that take us to exotic locales, such as Vietnam during the fall of Saigon, Grenada as the U.S. invades, and New Orleans with its pub crawls and transsexuals. The stories are compiled from our own recollections and those of Hunter’s other close friends and neighbors, people who tend to keep their memories private, but who disinterred them for us. The stories span a period from 1968, when Hunter first arrived in Woody Creek, delivering a load of furniture for art dealer Patricia Moore, to the day of his death. They deal with his 3:00 A.M. phone calls to discuss vital, urgent, matters such as…firewood—and the 5:00 A.M. drive-bys, with Hunter leaning on the horn in the predawn darkness and pitching explosives out the window of his car. His idiosyncrasies and bizarre habits are explored at length and in depth. We’ll both be writing first-person accounts of our adventures with Hunter, so we’ll identify who’s speaking (Braudis or Cleverly) at the beginning of the chapters. The stories that are a result of our interviews with others close to Hunter are written in the third person.

The kitchen in Hunter’s cabin at Owl Farm was a simple knotty-pine affair, both the walls and the cabinets. A few years ago the pine cabinets were replaced with cherry, but the walls remained knotty pine, with vintage orange shellac. Hunter’s famous counter stretched across two thirds of the kitchen. Behind the counter sat Hunter, and behind Hunter were the range, the sink, countertop, and assorted cutting boards. Cooking on the range essentially put you back to back with Hunter, a dubious honor or a dangerous position, depending on his mood. The couch was backed up against the front of the counter so everyone was facing the same direction: the TV. The only other stool at the counter, besides Hunter’s, was just to Hunter’s left. That stool was always occupied by the person highest in Hunter’s pecking order, the sheriff, if he was in attendance. The regulars knew to vacate it when a higher-ranking crony entered the kitchen; newcomers had to be told. Next to that stool was an exercise bicycle. Ostensibly it was there so Hunter could just hop on and get a bunch of exercise, Hunter not being one to go charging off to the gym. It must be reported that Hunter had been seen on the thing, but exercise isn’t the word to describe what he was doing. We old-timers weren’t too fond of it, but younger guests thought it was pretty cool and would cheerfully jump on and pedal away. There was one easy chair that also faced the TV. Next to the television was the upright piano; in all those years, no one seems to remember ever having heard one note out of it. When Hunter was working on a major project he’d have a large corkboard hung in front of the piano, which would fill up with notes for the book, as well as random aphorisms and bits of pornography. The kitchen would morph to meet the requirements of the event at hand, with more furniture being hauled in so the maximum number of people could be jammed in to watch the Kentucky Derby, Super Bowl, or perhaps presidential debates.

The living room was through the door next to the piano. It was a nice large room, especially considering Hunter’s cabin wasn’t particularly huge. A big fieldstone fireplace dominated one end. The wall to the right, as you entered from the kitchen, had the front door and picture windows looking out on the deck and the peacock cage. The room was full of books, plus stuffed animals, skulls, and the sort of exotic memorabilia that people associate with Hunter S. Thompson.

Election Night was always huge at Owl Farm. Some ended well. Some not so well. I think Hunter just kept the pool money from the 2000 election that took so long to resolve.

An old friend, who goes way back with Hunter, explained why that big comfortable room wasn’t the center of activity at Owl Farm. It started years ago, when Hunter was between girlfriends and couldn’t afford someone to keep house for him. Everyone used to hang out in the living room, but it got to a point where no one had cleaned it up for weeks, maybe months, and it had devolved into an utterly squalid, fetid, pigsty. There were decaying turkey carcasses, which were convenient to snack on for the first few days but started to smell like corpses after a while. Half-eaten ham sandwiches lying around that you’d remember as having been in the same place on your last visit, and all the other general trash and debris of daily living. Hunter didn’t have a very good sense of smell; maybe he was just oblivious to all of it. Ultimately it was easier to just move to the kitchen than it would have been to tackle that god-awful mess. Once the scene moved into the kitchen, it never moved back.

For the big Kentucky Derby and Super Bowl parties, the TV from Hunter’s bedroom would be hauled into the living room. The buffet would be set up in there, and that’s where the overflow would watch the game. Those of us who spent as much time in Doc’s kitchen as we did our own homes would often opt for the living room, as the kitchen would fill up with acolytes and first-timers desperate to be close to him.

Usually the people assembled at Owl Farm fit quite comfortably into the kitchen. When things became uncomfortable there, it wasn’t due to overcrowding; that would have been too simple. It was because someone was making things uncomfortable. It was something Hunter was very good at.

The good folk of Woody Creek were proud of the fact that Hunter Thompson called their little village home. Woody Creekers are famous for having a set of values different than those of the people up the road in Aspen, and they go out of their way to demonstrate it every chance they get. They embraced Hunter, and he was a good neighbor. He didn’t care if you were of the same political stripe as he was, or if you shared his hobbies or leisure-time activities; being a neighbor was different from being a crony; a neighbor was a neighbor no matter what. That feeling was reciprocated. People who were political opposites of Hunter, who would never have joined us in the kitchen for a game or other dubious behavior, felt very warm toward him because they knew he truly was a good neighbor who was cordial and courteous and could be counted on if he were needed.

Hunter felt safe in Woody Creek. T

hose around him always respected his privacy and would insulate him from outsiders who might try to intrude. You could never get directions to Owl Farm from a Tavern bartender. If a pilgrim set on meeting Hunter seemed overly persistent, a call would be made and someone, such as Cleverly, would appear to do the screening. It would be explained to the individual that he hadn’t been asked to come to Woody Creek, and that the thousands of miles that he might have traveled to worship at the altar of “gonzo” were irrelevant. Doc wasn’t interested. If a reasonable chat didn’t work, there was always the Sheriff.

No matter how exotic or glamorous Hunter’s journeys, he always looked forward to his return to Owl Farm, Woody Creek, and the company of his small circle of trusted friends. These are their stories. These tales aren’t necessarily the outrageous “gonzo” stuff that people tend to write, and that fans expect to read, about Hunter. Often funny, sometimes poignant, these stories are the real Hunter, the private Hunter. Hunter was a gentleman; he would always rise when a woman entered the room and would always greet someone new with courtesy and decorum. Hunter was a well-bred Southerner with good manners, and that was important to him. When, upon occasion, those manners weren’t apparent, it wasn’t because he’d forgotten them. He could also be the madman his fans envisioned, the one portrayed in film and in Ralph Steadman’s brilliant illustrations. He was also a friend, a husband, and a father.

The Kitchen Readings

The Kitchen Readings